“We are the first generation to feel the sting of climate change, and the last generation that can do something about it.”

An Introduction to Climate Policy

Despite the optimistic nature of climate policy, we are regrettably finding ourselves in a phase of ineffective action, or simple inaction. Although we are aware of the need to limit global warming to 2°c below pre-industrial levels, there isn’t much urgency to do what is necessary.

Yes, there have been some small victories here and there but ultimately the complete picture still remains but a sketch of an unfinished work. Sadly, this work remaining unfinished could have more dire consequences than we might care to think about.

Where is the Systemic Change?

Current climate policy takes quite a relaxed approach, and considering the nature of changes required, this makes sense as anything more drastic would absolutely lead to backlash among us common folk. Though perhaps such changes are needed.1

However, for the purposes of this article I will look to be a little less political in my understanding and try to look at the situation through a lens of necessary change, despite the real-world application of such change being unrealistic. Furthermore, I will focus exclusively on the EU and their now estranged cousin, the UK. As both have their own policy on climate action aimed to transform the landscape, those being the European Green Deal2 (EGD) and the Net Zero Strategy (NZS) respectively.3

A Closer Look at These Policies

Both the EGD and the NZS share very optimistic language. Like most policy that involves difficult change, wording of such things is best done to make us believe we are to be a part of a great innovation. The EGD promises us an inclusive and “symbiotic” transition to net zero emissions, all the while protecting the rights of their citizens, and simultaneously ensuring economic growth.4 The NZS makes similar statements, such as ensuring climate commitments are met without sacrificing life’s luxuries.5

Unexpectedly these promises offer a win-win for all involved. This though is where the problem lies, because realistically if such a transformation were as painless and innovative as the wording suggests, why has progress been so slow?

It is unlikely that reaching a net zero utopia would be so easy to have both zero emissions and no loss of the life we have been accustomed to. The reality is likely far more daunting than climate policies care to admit.

Implementing effective policy with as much impact as is being claimed in the EGD and NZS could be riddled with legal and political dilemmas which would create inevitable winners and losers.

Dilemmas

The first, more obvious, type of dilemma comes from conflicting targets. For example, companies may find it hard to meet their plastic production targets, while simultaneously implementing a strong plastic intervention policy. Similarly, how does a nation meet oil and gas energy security while also decarbonizing.6

We can consider this a conflict of policy. This is to be expected, considering climate action is fairly new, and contracts and targets for fossil fuels and energy have been long standing. Such things could be worked around with time and additional policy.

However, conflicts can extend beyond policies, leading to conflict of interests. This has been evidenced among fossil fuel groups, such as Shell and ExxonMobil.7 Understandably, these corporations have no interest in oil and gas usage being lowered. As a result, we have seen considerable sums of money being sunk into lobbying efforts to delay or block climate action from these groups.8 These efforts are reminiscent of the various lobbying strategies made by the tobacco industry,9 whereby the WHO had to implement an article in the FCTC,10 specifically urging countries to protect their health policies over the interests of the tobacco industry.11

If we prioritise decarbonisation without addressing economic strain, we’ll risk further harming already vulnerable communities. Alternatively, nations might increase reliance on fossil fuels until the climate action policy transition becomes more feasible. The UK attempting to develop a new coal mine project hinted at this uneasy compromise, however, the high court ruled that such a development would go against net-zero policy and was subsequently blocked.12 The relevance here is that the situations are not dissimilar. A huge industry is making efforts against policies that will harm their profit margins, placing their business above the health and safety of the people. If we consider CO2 emissions the equivalent of the earth smoking an earth sized giant cigarette, we can see the similarities. We can see similar conflict of interests when parties to international climate treaties attempt to undermine climate action progress if it should affect their state-owned companies negatively.13 Examples can be seen from various countries attempting to weaken the IPCC‘s recommendation to move away from fossil fuels.14

Energy Poverty

To complicate matters more, we are currently dealing with an energy poverty crisis. The UN have reported that at least 1.18 billion people worldwide struggle to reliably afford basic energy needs like heating, lighting and gas for cooking.15 This has only been worsened by geopolitical issues like the ”special military operation” (war) between Ukraine and Russia. It also does not help that, despite the political and financial support the EU has given to Ukraine, they also have energy demands at home that need to be met. The source of the energy is of course Russia, which means they have found themselves funding both sides of the war.16

Unfortunately, this creates some degree of legal, and ethical, complications. In particular, since the annexation of Crimea (2014) the EU had imposed various sanctions on Russia, including restrictions on Russian oil and gas sales.17 Yet, the purchase of said oil and gas has hardly seen a decrease in volume. The Treaty on European Union also creates sanctions and obligations against those found violating international law.18 Furthermore, the International Law Commission’s articles on state responsibility hold similar sanctions for any country found aiding another in what might be considered a wrongful act, this includes acts of aggression.19 Considering the UN has already condemned Russia’s invasion,20 and the EU has politically backed Ukraine by sending aid, we must now question whether the EU is indirectly aiding an internationally wrongful act, and if so, they are violating their own treaty obligations.

But ultimately, as mentioned above, we are now seeing another form of conflict of interest. The EU must meet their energy demands, and Russia is the country that can do that for them, despite condemning their actions. Without doing so the citizens of the EU might find themselves deeper into energy poverty.

Despite the strong need to decarbonize more aggressively, doing so would cause significant strain on already vulnerable communities. But from the perspective of a healthy planet, it is something that would be necessary. This is the crux of the issue of both the EGD and NZS, the rose-tinted lens they view the situation through does not allow for losers, but if the need to achieve the targets of the Paris Agreement were placed as the priority, losers are unavoidable. But to view the world from such a utilitarian perspective is completely unrealistic, and ethically questionable.

Due to these circumstances, we have found ourselves in climate action policy has become a target for populist movements, which could lead to legal and political foundations becoming fragmented. Therefore, we must approach with caution.

The Role of Targets and Policy Enforcement

I explore thoroughly the ins and outs of Nationally Determined Commitments through the Paris Agreement here, but the long and short of it is that each country sets their own targets, with these expected to grow bolder after every iteration.21 We can see a very recent example of this in COP29, where the UK made an extremely optimistic target of an 81% emissions reduction. Although I applaud the goal, it is somewhat questionable. The UK has no real ”plan” to achieve it, as well as making contradictory commitments, such as the Heathrow runway expansion.22

Again, this is another conflict of interest. But it also highlights the issue with targets, particularly those made in the Paris Agreement, as there are no repercussions should they not be met. Without legal intervention, it will be very difficult to actually achieve the targets countries are being applauded for making.

Legal Intervention

Though I have blabbered on about the real issues stemming from this transition, I cannot ignore that the EGD does explicitly acknowledge socioeconomic challenges arising from this transition to lower emissions.23 Which is why they have created the Just Transition Mechanism (JTM), allocating 55 billion euros to ease any such economic strain placed created.24

While the NZS isn’t quite as explicit in its wording, opting for a ”levelling up” agenda, which mentions relatively vague economic and moral programmes as means of support.25 However, both of these policies hope to improve the living standards for all involves, through investments into ”green technology”.26 Although, what is considered ”green technology” is still quite vague, as what is considered green technologies is never defined.

Greenhouse Gas Removal?

The technical limitations of these policies come to a head when we consider the actual reality of attempting to lower emissions. If we are to assume that the green technology investments mentioned in the EGD and NZS refers to Greenhouse Gas Removal (GGR) technology, then we have another issue.

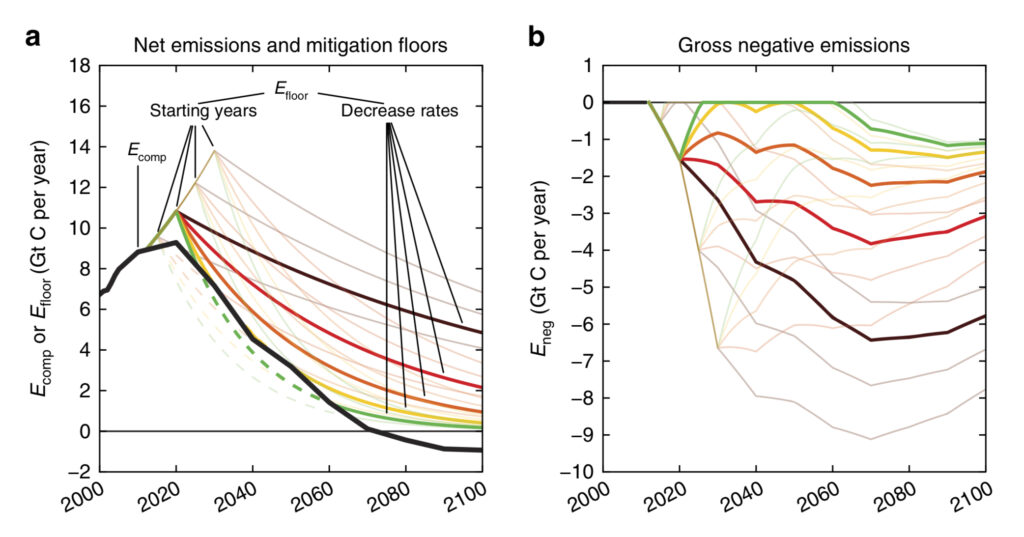

Theoretically it makes sense, GGR or Greenhouse Gas “capturing” could be used to counterbalance increased, or sustained, fossil fuel use. However, the ratio of creation and reduction of emissions is not equal. Meaning, if this technology is to be relied upon in these policies, we need significant advancements in the technology. Without it we must reduce emissions overall.27

On the other hand, it has been argued that any policy that does not rely on such technology will have uncertain effectiveness, given the nature of the Earth can only be predicted, but prediction does not equal certainty.

But GGRs will still be met with legal and practical implications, even if the IPCC themselves admit their use is necessary and unavoidable.28 Some have even gone as far as to say they are ”market fiction”, believing that their use and reliance would only interfere with genuine efforts to lower emissions naturally.29 One of the major concerns is allocating land for this technology, which may conflict with essential needs such as agriculture, housing, and ironically power. All of which are just as important with an ever-growing population.30

Though GGRs are not likely the panacea to the problem, at the very least they can act as a safety net should any plans to naturally lower emissions ”run amok”.31

Navigating the Crossroads of Ambition and Reality

Although the targets set out seem very noble and inspiring, repeated failure to meet them, as well as conflicting interests from all angles creates major issues when creating and implementing effective climate policies. Thus far we have only seen colliding environmental interests and socioeconomic needs. Sadly, green technology cannot be relied upon in the way we hope. Even greener sources of power, such as hydropower, is harmful to water quality and aquatic habitats.32

Therefore, it is understandable to see politicians opting for optimistic targets and policies, but I fear the reluctance to face hard truths only harms our progress to decarbonize effectively.

- United Nations Environmental Programme, Emissions Gap Report 2022: The Closing Window (UNEP, Kenya, 2022) xxii ↩︎

- The European Green Deal [2020] accessible: https://www.esdn.eu/fileadmin/ESDN_Reports/ESDN_Report_2_2020.pdf ↩︎

- Net Zero Strategy accessible: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/6194dfa4d3bf7f0555071b1b/net-zero-strategy-beis.pdf ↩︎

- EGD (n 3) ↩︎

- HM Government, Net Zero Strategy: Build Back Greener (October 2021), foreword ↩︎

- ‘Legal Dilemmas of Climate Action, Journal of Environmental Law’ Vol 35 1 (2023) 1 – 9, available https://doi.org/10.1093/jel/eqad007 ↩︎

- Conflicts of Interest and Undue Influence in Climate Action, Transparency International (2021) available https://images.transparencycdn.org/images/2021_ConflictsOfInterestClimateAction_PolicyBrief_EN.pdf ↩︎

- ibid 3 ↩︎

- S. Ulucanlar, G.J. Fooks, A.B. Gilmore, The Policy Dystopia Model: An Interpretive Analysis of Tobacco Industry Political Activity, PLoS Medicine, 2016, 13(9): e1002125, doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1002125 ↩︎

- WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control & World Health Organization [2003] ↩︎

- World Health Organization, Guidelines for implementation of Article 5.3 of the WHO FCTC, 2008/2013 ↩︎

- Euronews, ‘UK high court blocks first new coal mine in 30 years. Is it the end of the ‘climate-damaging’ plan?’ accessible here ↩︎

- ibid ↩︎

- https://unearthed.greenpeace.org/2021/10/21/leaked-climate-lobbying-ipcc-glasgow/ ↩︎

- Brian Min, et al ’Lost in the dark: A survey of energy poverty from space’ Joule Vol 8, 7 (2024) https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joule.2024.05.001 ↩︎

- Vaibhav Raghunandan, et al ’EU imports of Russian fossil fuels in third year of invasion surpass financial aid sent to Ukraine’ Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air (2025) ↩︎

- Council Regulation (EU) No 833/2014; see also Council Decision (CFSP) 2022/266 ↩︎

- Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, art 21 & 29, 2012 O.J. (C 326) ↩︎

- Draft Articles on Responsibility of States for Internationally Wrongful Acts [2001] Article 16 & 41 ↩︎

- UNGA Resolution ES-11/1 [2022] per Article 2(4) of the UN Charter ↩︎

- Paris Agreement (n 1) Article 4 ↩︎

- Government update on airport expansion, available here ↩︎

- EGD section 2, 16 ↩︎

- ‘The Just Transition Mechanism: making sure no one is left behind’ accessible here ↩︎

- ‘Levelling Up the United Kingdom’ various versions accessible here ↩︎

- Legal Dilemmas (n 3) ↩︎

- T Gasser, et al. ‘Negative Emissions Physically Needed to Keep Global Warming Below 2°C’ Nature Communications (2015) ↩︎

- IPCC Working Group III (2022), Technical Summary. In: Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change. Sixth Assessment Report ↩︎

- Legal Dilemmas (n 3) ↩︎

- Climate Change Committee Report, Progress in reducing emissions (June 2022 Report to Parliament) at 25 and 28, available here ↩︎

- Gasser (n 22) ↩︎

- Commission v Austria and Case C-529/15 Folk ↩︎